What's next as Iraq moves to end deadlock?

Iraqi lawmakers have elected a new president who swiftly named a prime minister in the hope of ending a year of political gridlock and deadly violence.

But major challenges lie ahead for the crisis-hit nation.

- How will government talks play out? -

Iraq's parliament, dominated by the pro-Iran Coordination Framework of Shiite Muslim factions, elected on Thursday a new president, 78-year-old Kurdish former minister Abdul Latif Rashid.

The new head of state moved immediately to task Shiite politician Mohammad Shia al-Sudani with forming a government, capping a whole year of deadlock between major parties since Iraq last went to the polls in October 2021.

In multi-ethnic, multi-confessional Iraq, where political alliances and coalitions constantly shift, divisions between feuding factions might resurface and complicate Sudani's efforts in the 30 days afforded to him to form a government capable of commanding a majority in parliament.

In the past, constitutional deadlines have been routinely missed amid protracted political wrangling.

"Once we start discussing who becomes minister, but even more critically who gains more leverage over the senior civil service, government agencies, state coffers -- that's when we will continue to see the fragmentation and stalemate play out," said Renad Mansour of British think-tank Chatham House.

He explained that Iraq is headed for "another power-sharing government", where political parties will "try and divide the country's wealth".

And the stakes are high. A colossal $87 billion in revenues from oil exports are locked up in the central bank's coffers.

The money can help rebuild infrastructure in the war-ravaged country, but it can only be invested after lawmakers approve a state budget presented by the government, once formed.

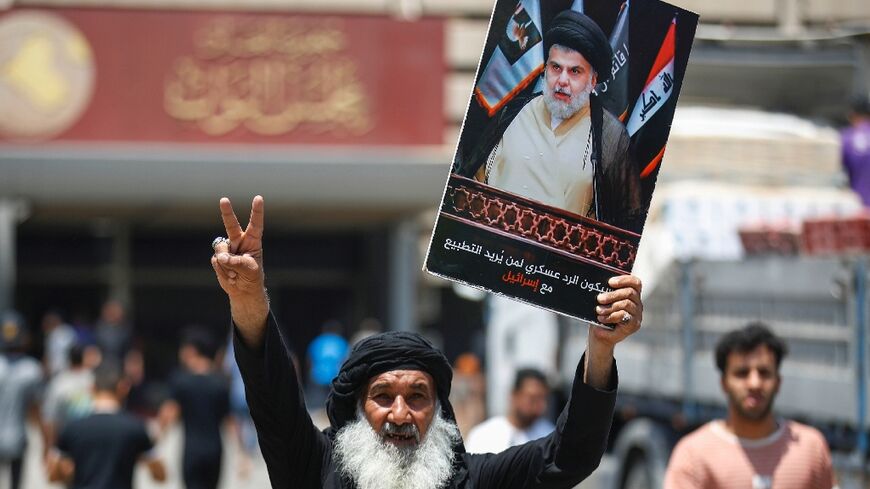

- What will Sadr do? -

The future government's hands may be tied by influential Shiite cleric Moqtada Sadr, capable of mobilising tens of thousands of his supporters with a single tweet.

In June, he had ordered the 73 lawmakers in his bloc to resign, leaving parliament in the hands of the rival Coordination Framework, which now controls 138 out of 329 seats in the legislature.

This pro-Iranian alliance includes the political arm of the former paramilitary Hashed al-Shaabi, as well as Sadr's longtime rival, former prime minister Nuri al-Maliki.

Political analyst Ali al-Baidar noted the Sadrist movement has kept uncharacteristically "quiet".

It may be that their leader has been "giving the political forces a chance", but it could also be the result of "an agreement offering the movement some" government positions in return for their tacit approval of Sudani's nomination, Baidar said.

Tensions between the two rival Shiite camps boiled over on August 29 when more than 30 Sadr supporters were killed in clashes with Iran-backed factions and the army in Baghdad's Green Zone, which houses government buildings and diplomatic missions.

"It remains a precarious state of affairs," Mansour said.

"Sadr will remain on the margins of the political scene, trying to disrupt and use protests to replace the political capital" he lost in parliament, the researcher added.

Sadr is "hoping to force an early election using controlled instability as he always has, to maintain his power and leverage in negotiations.

"But mistakes in the past few months have... put him in a difficult bargaining position," Mansour continued.

- Is there hope for change? -

Political analyst Baidar said the "consensus" on Rashid's appointment means a government will be formed relatively easily, but stressed the "colossal tasks" ahead.

Nearly four out of 10 young Iraqis are unemployed and one-third of the oil-rich country's population of 42 million lives in poverty, according to the United Nations.

Prime minister-designate Sudani vowed on Thursday to push through "economic reforms" that would revitalise Iraq's industry, agriculture and private sector.

He also promised to provide young Iraqis "employment opportunities and housing".

According to Baidar, a "growing" global interest in Iraqi politics -- specifically from Washington, Paris and London -- could "force politicians to perform better".

"While Iraq is by no means a poor country, private and partisan interests conspire to divert resources away from critical investment in national development," UN envoy Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert told the Security Council last week.

"Iraq's political and governance system ignores the needs of the Iraqi people," she charged.

"Pervasive corruption is a major root cause of Iraqi dysfunctionality. And frankly, no leader can claim to be shielded from it."

A pessimistic Mansour said "public life will remain as it is".

"People will still not have their basic rights, water, healthcare, electricity."