In search of Jewish heritage in Morocco's southern oases

In the depths of Morocco's Akka oasis, two archaeologists pore over the floor of a synagogue searching for the minutest of fragments testifying to the country's ancient Jewish history.

They are from a team of six researchers from Morocco, Israel and France, part of a project to revive the North African country's Jewish heritage after it was all but lost following the minority's exodus.

The discovery of a fragment of a Hebrew religious manuscript is "a sign from above", jokes Israeli archaeologist Yuval Yekutieli, from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Efforts to uncover Jewish historical treasures scattered across the kingdom's oases are one of the outcomes of warming ties since Morocco and Israel normalised relations in 2020.

Akka, a lush green valley of date palms surrounded by desert hills some 525 kilometres (325 miles) south of the capital Rabat, was once a crossroads for trans-Saharan trade.

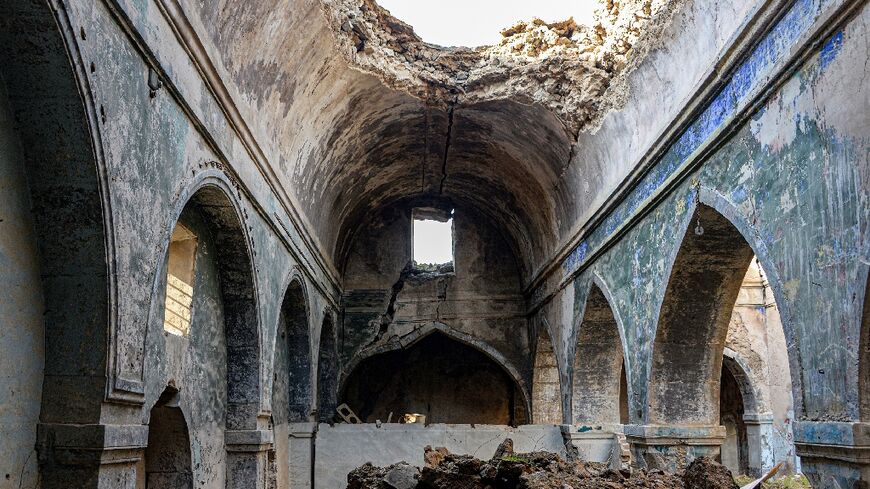

Within the oasis, tucked away in the middle of the "mellah" or Jewish quarter of the village of Tagadirt, lie the ruins of the synagogue -- built from earth in the architectural tradition of the area.

While the site has yet to be dated, experts say it is crucial to understanding the Judaeo-Moroccan history of the region.

"It's urgent to work on these types of vulnerable spaces that are at risk of disappearing," said Saghir Mabrouk, an archaeologist from Morocco's National Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (INSAP).

- Looting -

Dating back to antiquity, the Jewish community in Morocco reached its peak in the 15th century, following the brutal expulsion of Sephardic Jews from Spain.

By the early 20th century, there were about 250,000 Jews in Morocco.

But after waves of departures with the creation of Israel in 1948, including following the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, the number was slashed to just 2,000 today.

Little documentation remains of the rich legacy that the community left behind.

"This project aims to study this community as an integral part of Moroccan society, and not from a Judaeo-centric perspective," said Israeli anthropologist Orit Ouaknine, herself of Moroccan roots.

As the day progresses, the archaeologists amass a small trove of manuscript fragments, amulets and other objects discovered under the "bimah", a raised platform in the centre of the synagogue where the Torah was once read.

Yekutieli, the Israeli archaeologist, said the "most surprising thing" was that no one had written about the buried objects, and that it was only when excavations began that they were discovered.

While Jewish tradition dictates that such texts are never destroyed, it is unusual to find them buried at such sites.

Among the artefacts unearthed and meticulously catalogued by the team are commercial contracts and marriage certificates, everyday utensils and coins.

The synagogue had already begun to fall into disrepair when looters attempted to raid the buried cache.

"The good news is that one of the beams collapsed, making access difficult," said Yekutieli.

A similar looting attempt was recorded at the ruined synagogue of Aguerd Tamanart, sited in another oasis some 70 kilometres (45 miles) southwest of Akka, where excavations began in 2021.

In this case, the artefacts were not buried but rather hidden in a secret compartment behind a collapsed wall.

The team was able to save the majority of the objects, some 100,000 pieces including fragments of manuscripts and amulets.

- 'Precious testimonies' -

At both sites, architect Salima Naji has led efforts to restore the earthen monuments, being careful to remain faithful to the traditions of the desert region.

"More than 10 years ago, I began by recreating the typology of all the synagogues of the region," she said.

"My experience in rehabilitating mosques and ksour (fortified villages) helped me to better understand that of the synagogues."

Restoration is still underway in the Tagadirt synagogue, where Naji's team is hard at work to reconstruct the skylight that illuminates the building.

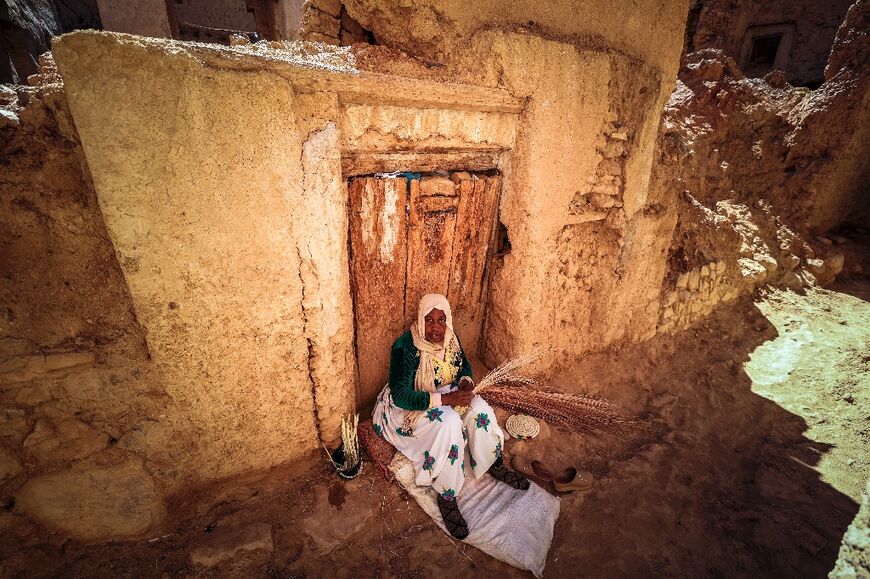

Today, the Muslim inhabitants of the former Jewish quarter welcome the restoration.

"It's a good thing not to leave the synagogue abandoned," says craftswoman Mahjouba Oubaha.

The excavation has just begun to scratch the surface of knowledge about Morocco's Jews, shedding light on their daily objects and way of life.

Orit Ouaknine said she conducted interviews with the former Jewish residents of the two villages, now living in Israel, the United States and France.

"It's a race against time to collect these precious testimonies," the Israeli anthropologist said.