Survivor seeks to retell Hamas attack with WhatsApps

Message after message, the brief WhatsApps tell a poignant and chilling story of encroaching terror with people making increasingly desperate pleas for help, some of them with only minutes to live.

"People documented their last moments, they sent selfies before they were murdered," said Yaniv Hegyi, a former secretary-general of kibbutz Beeri.

Beeri was the worst-hit community in the Hamas attacks of October 7 on southern Israel, second only to the Supernova music festival for the number of victims. Out of a population of 1,100, more than 80 were killed.

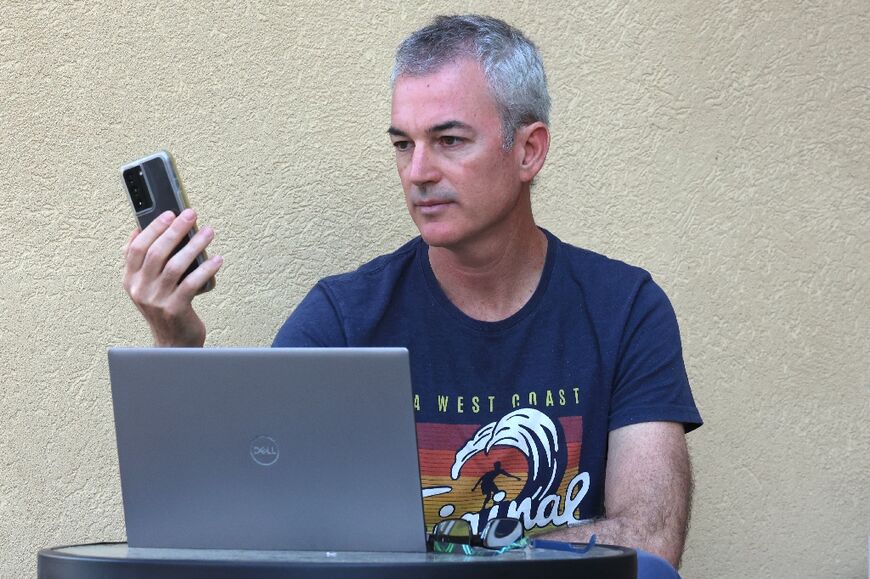

Now Hegyi is leading a project called "Memorial 710", collating the WhatsApp messages, images and video sent that day to create a second-by-second archive of the bloody attack as gunmen overran the rural community.

For the terrified residents hiding in their safe rooms in the dark, their mobiles were their only source of information and communication.

"Where's the army? They're breaking into our home!" read one message Hegyi showed AFP.

"There's shouting in Arabic... there's a lot of shooting," said another. "Please come, it's urgent."

"They're shooting at the door."

In one instance, Hegyi -- who was in dozens of WhatsApp groups as a result of his position, and received thousands of messages that day -- wrote back: "Stay inside, don't go out.

"Everyone who goes outside the house gets killed."

- 'Mum's been killed' -

The October 7 attacks saw 1,200 people, mostly civilians, killed and some 240 others kidnapped, according to Israeli officials.

Soon after, global attention quickly switched to Israel's retaliatory bombardment of Gaza, which has claimed nearly 16,000 mostly civilian lives according to the latest toll from the Hamas-run health ministry.

"Within days the narrative changed and it's almost like we have to fight for the truth of what happened," Hegyi said.

By "a miracle", the 50-year-old and all his family survived. Along with many Beeri survivors, he has been housed temporarily at kibbutz Ein Gedi by the Dead Sea.

He visualises an interactive map of the entire area invaded by militants where future researchers could select a kibbutz, neighbourhood or home, and pull up related WhatsApp messages, photos and videos from the attack.

"So if a 13-year-old girl sent me a voice note saying: 'Please help, mum's been killed, my brother's dead and dad's very badly hurt', they could jump to her safe room and see what happened with them on that day and about her dad -- who is still alive," Hegyi said.

"They will be able to move from place to place through the WhatsApp network and see what really happened on that day," he added.

"This is our story."

- Excruciatingly personal -

Beeri resident and former historian Hana Brin, 76, said she agreed to share her messages because of the importance of the historical record.

The collection of WhatsApps "is completely different from any other documentation which happens after a week or two or even a year later," she said.

"It's the most authentic documentation because it's in real time, in the place where it happened and under great distress," she said.

"That's the most direct you can get about what happened."

Raquel Ukeles, head of collections at Israel's National Library, which is creating a huge archive and database of material linked to October 7, said such messages were "extraordinarily valuable for researchers".

They assist with recounting and analysing the events, and also "defend the historical accuracy against denial and outrageous claims of 'fake'," she told AFP.

"But it's intensely, excruciatingly personal."

So far, 100 Beeri survivors have agreed to participate in "Memorial 710" and volunteers are asking other communities to join in before the messages get lost in the ether.

There are technological challenges in effectively storing messages, images and videos while also respecting privacy and confidentiality.

Even harder is persuading survivors to share deeply personal and painful messages -- often the last words between loved ones.

"It's not easy to convince them to join the project," Hegyi said. "But when they do, some sort of magic happens.

"When they give up their WhatsApps, they are doing something proactive, they're freeing themselves from that sense of powerlessness we all felt inside the safe rooms."