Middle East crises loom in background as NATO leaders gather in Washington

While this year's summit is expected to focus largely on the ongoing war in Ukraine, Iran's military support for Russia and Turkey's strategic balancing act with Moscow are expected to weigh on NATO leaders gathered in Washington.

WASHINGTON — US and European leaders are expected to focus largely on the war in Ukraine as they gather in Washington this week for the annual NATO summit and the 75th anniversary of the alliance.

But nascent and reemerging conflicts in the Middle East and Pacific continue to loom in the background as the Biden administration seeks to build faith among its allies in hopes of shoring up Washington’s influence around the world.

While the epicenter of the NATO summit's focus remains in Europe, the increasing internationalization and hybridization of warfare has complicated its members' obligations and blurred the boundaries of traditional nation-state alliances.

The alliance aims to strengthen its cyber, space and undersea defenses, and will also stand up a new command at Wiesbaden, Germany, to help train and develop Ukrainian military forces and serve as a bridge to Kyiv’s eventual membership into the alliance.

Last week the United States announced its largest tranche of military support for Ukraine, totaling more than $4 billion. The package is expected to fund National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMs) and other air defense systems intended to help the country better defend against Russian barrages, which have been made more lethal by thousands of Iranian-made Shahed drones.

Washington’s efforts to choke off Iran’s supply of precision one-way attack drones haven't prevented it from forging a partnership with Moscow to mass-produce them. And the US-led economic isolation of Russia over its invasion of Ukraine has resulted in Moscow strengthening its strategic ties with Iran and Beijing, all while US sanctions have been undermined by Turkey, home to the second-largest army in the NATO alliance.

Both Tehran and North Korea have directly provided Russia with military hardware to bolster its war in Ukraine, including armed drones and artillery shells, raising concerns that Moscow could return the favor with advanced weapons technology that could potentially heighten nuclear threats.

The Biden administration has also been attempting to reel in Israel’s war in the Gaza Strip to avoid a wider regional conflict that could potentially draw in Iran, which possesses ballistic missiles that can range parts of Europe.

Iran’s continuous expansion of its enriched uranium stockpiles drew European states in April to convince the Biden administration to censure the Iranian government.

“What’s happening now in the Middle East is of course of concern to all NATO leaders,” Michael Carpenter, the senior director for Europe at Biden’s National Security Council (NSC), told reporters during a press briefing on Monday.

The icy ties between the United States and Turkey in recent years over Ankara’s purchase of Russian air defense systems have thawed somewhat. Early this year, Washington's no.-2 top diplomat once again floated the possibility of renewing top-tier defense ties with Turkey if it were to mothball its S-400 system.

The Turkish government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has unsubtly played its own hand within the alliance to build clout, blocking the historic accession of Finland and Sweden for more than a year in a bid to gain concessions toward a crackdown on left-wing Kurdish activists in Europe, whom Turkey's government considers terrorists.

During last year’s summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, Al-Monitor exclusively reported that Ankara had also held up the alliance’s attempts to update its collective defense strategy, demanding the document rename key maritime waterways around Turkey to “Turkish Straits.”

Due in part to Turkey’s renewed strategic importance to the West amid Russia’s war in Ukraine, American diplomats have pursued an increasingly realpolitik approach to Ankara, with less the fealty of a dedicated ally than the deference and pragmatism of an indispensable frenemy.

“Obviously Turkey is a critical ally. They sit at a very important juncture, both in terms of the Eastern Med[iterranean], in terms of the South Caucuses, in terms of the Black Sea,” Carpenter told reporters Monday.

As NATO embarked on an historic expansion on the Baltic flank over the past two years, doubling the alliance’s shared border with Russia, Biden administration officials have sought to expand other defensive partnerships elsewhere in the world outside of the formal alliance structure.

The policy aims to replicate similar strategic benefits for Washington by capitalizing on the allure of unmatched US military power in order to compensate for its waning relative economic clout in a bid to cement American influence.

The Biden administration invited a wide swath of aligned nations that are not part of the formal alliance, including several Middle Eastern states — Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain and Jordan among them, the Financial Times previously reported. Qatar and the Bahrain were expected to send representatives.

The unusually broad invite came as Washington seeks to shore up Europe’s defenses via the formal alliance structure while bilaterally bolstering defense and economic throughout the Pacific and Middle East, both as a bulwark against Russian, Iranian and Chinese hybrid military threats, and also to blunt Beijing’s global economic strategy in those regions.

US and Middle East policy makers have kept their eye on the UAE in particular as a potential nexus of Beijing's influence in the region.

“We’re in a different era, worldwide,” said Biden administration’s energy envoy, Amos Hochstein, who brokered a resolution of the maritime border dispute between Israel and Lebanon last year.

“Every secretary of state likes to say ‘economic policy is foreign policy,’ but they rarely work toward that. We’re in an era now where … it’s the main driver,” Hochstein said during a virtual think tank event in Washington last month.

“If you look at what’s happening in the Gulf, you can see the Gulf involvement in other countries. … I look at the supply chains and the investments that China is making, that Russia is making, the Gulf is making and the United States — this is what it’s all about,” he added.

Biden elevated Qatar to the status of "major non-NATO ally" in 2022.

Last year, the Biden administration signed a new defense partnership with Bahrain — home to the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet — in what American officials described as a “template” for further defense agreements in the region.

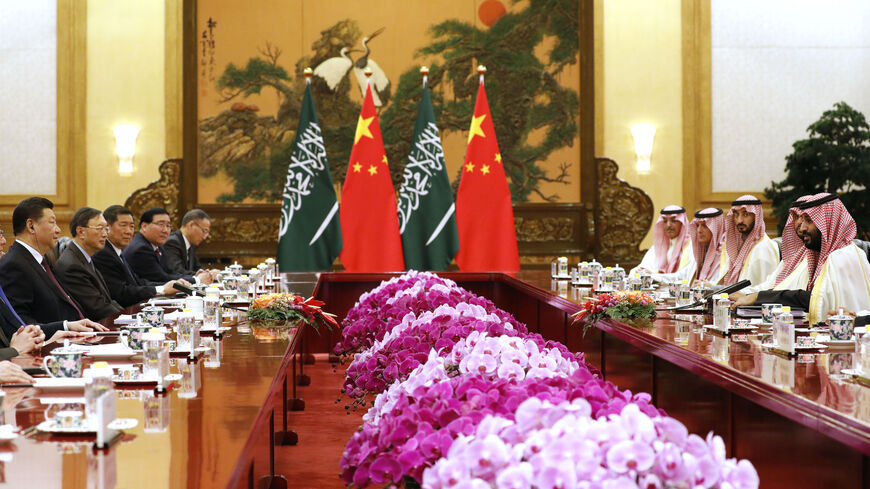

Yet the ultimate prize for shoring up US influence in the region — Saudi normalization with Israel — remains elusive, dependent on the current right-wing Israeli government’s willingness to make concessions to the Palestinians. Riyadh is demanding a formal defense pact with the United States, which congressional lawmakers are almost certain to block unless Saudi Arabia establishes ties with Israel.

Saudi officials will not be attending the NATO summit, a source familiar with the matter said.