CT scans reveal mysteries of ancient Egypt's 'Screaming Woman' mummy

Al-Monitor interviewed Cairo University radiology professor Sahar Saleem on her high-tech research into this unique mummy.

CAIRO — An 1935 expedition in Luxor unearthed a mummified female at Deir el-Bahari, a tomb complex in the Theban Necropolis, that attracted attention due to the eerie description of the woman with her mouth wide open, as if frozen mid-scream. Technological advancements, in particular computed tomography, or CT, scans have recently permitted new research that provides fresh insights into who she is and what happened to her.

Cairo University radiology professor Sahar Saleem, who led the study of the so-called Screaming Woman, determined that she was around 48 years old at the time of her death, had back and dental issues, and was 1.54 meters tall. Her research on the mummy suggests that the woman's contorted face may have resulted from a cadaveric spasm, a condition in which muscles quickly become rigid immediately after death.

The woman's body has been exceptionally well preserved by the ancient embalming practices of Egypt's opulent New Kingdom era (1550–1069 BCE), which used luxurious ingredients such as juniper oil and frankincense resin.

The Screaming Woman was found in the family burial chamber of the architect Senenmut, who lived during the reign of Queen Hatshepsut (1479–1458 BC). She was likely a close family member of Senenmut.

In an interview with Al-Monitor, Saleem to dove deeper into her groundbreaking research, which was published Aug. 2 in the journal “Frontiers in Medicine.”

An 'elderly' woman

The use of CT scans provided Saleem a non-invasive opportunity to visualize the mummy in its entirety.

“I did the computed tomography scan for the mummy on a machine on a truck in the garden of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, one of the very few museums in the world that has its own CT machine,” Saleem said.

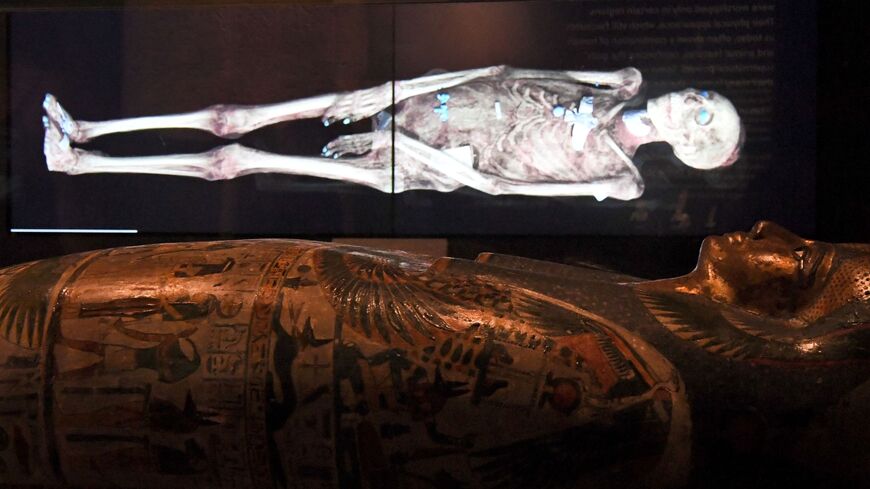

“The 2D and 3D images showed the mummy's physical features, health, mummification style, and its funerary accessory [a wig]. The mummy is well preserved,” she explained.

At 48, the woman was considered “elderly” in her day. According to Saleem, previous studies from ancient Egyptian cemeteries found anthropological evidence that led researchers to calculate the average life expectancy of females to be 35 to 37 years.

“She suffered from mild arthritis of the spine, as evident from the presence of osteophytes or ‘bone spurs’ on the vertebrae,” Saleem said.

She also noted several missing teeth, likely lost before death, as there was evidence of bone resorption, which occurs when a tooth is removed and the socket is left to heal. Other teeth were broken or showed signs of attrition, the wearing away of the surface due to tooth-to-tooth contact.

The teeth the woman lost while alive may well have been extracted. “Many [people] are in fact unaware that dentistry originated in ancient Egypt, with Hesy Ra being the first recorded physician and dentist in the world,” Saleem said.

A haunting expression

In addition to using CT scans, Saleem's team examined the woman's skin, hair, and wig using electron microscopy, FTIR analysis (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy), and XRD (x-ray diffraction). These techniques, like CT scans, are also noninvasive.

“There was no embalming incision, which was consistent with the discovery in CT images that the brain, diaphragm, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, and intestines were still present,” Saleem explained.

This, she said, was a surprise, because the classic method of mummification during the New Kingdom involved removing all the internal organs. That her organs were left in place would initially appear to suggest a poor or inexpensive mummification process, but as Saleem explained this is contradicted by the woman's body being so well preserved.

The Egyptians imported the expensive juniper and frankincense for embalming from other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean and from East Africa or Southern Arabia, respectively. The woman's natural hair had been dyed with henna and juniper.

“The presence of imported embalming materials provides insight into the scope of ancient Egyptians' international trade,” Saleem revealed. “They traveled to far-flung locations to bring back materials with the characteristics they sought to preserve the dead corpses for eternity.”

The imported embalming products highlight why proper mummification was a high-cost process and point to the woman's socioeconomic status, which afforded her the option of having the procedure.

“The golden and silver rings she wore, the wig she was wearing, and the painted wooden coffin in which she was interred all reflect her high socioeconomic status,” Saleem remarked.

It was previously thought that the mummy’s open mouth was due to poor mummification, but the expensive materials used in the woman's case and the mummy's well-preserved appearance rule out this theory.

“This opens the way to other explanations of the widely opened mouth — that the woman died screaming from agony or pain and that the muscles of the face contracted to preserve this appearance at the time of death due to a cadaveric spasm,” Saleem explained. “The story and circumstances of this woman's death remain unknown,” she added, having found nothing to possibly explain it.

Saleem said that cadaveric spasm is a unique form of muscle contraction that occurs just before death, triggered by intense physical or emotional stress. The phenomenon causes specific muscle groups to immediately stiffen after death, distinguishing it from generalized rigor mortis, which affects the entire body at a slower rate.

As for her expression, “It is possible that the contracted muscles prevented the embalmers from closing the mouth during the mummification,” said Saleem. The embalmers would have needed to mummify the body regardless of the position of the mouth before it decomposed.

The "Screaming Woman," found in Luxor in the Theban Necropolis, is now housed at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. (photo courtesy Sahar Saleem)

Expensive funerary attire

The Screaming Woman was adorned in fine funerary attire, including gold and silver jewelry and a palm fiber wig.

When asked about the significance of these items in ancient Egyptian burial customs, Saleem said, “The excavation notes mentioned that the ‘Screaming Woman’ was wearing two rings with jasper scarabs set on gold and silver rings, which are currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The scarab beetle was a symbol of resurrection in ancient Egypt. The material used for these amulets and jewelry denote the person’s wealth and socioeconomic status.”

Ancient Egyptians believed in resurrection and life after death, which is why they invented mummification — to preserve the body of the deceased for the afterlife. To prepare it for eternity, the embalmers clothed the mummified bodies and adorned them with jewelry and other apparel.

“The woman is wearing a long wig. Wigs and hair extensions worn by the living, [and also the dead] as burial apparel, illustrate ancient Egyptians' taste for ornament and beauty,” Saleem said.

“CT scans and analytical tests showed that the wig of the Screaming Woman, made from fibers from date palm, had further been treated with quartz, magnetite, and albite crystals, probably to stiffen the locks and give them the black color that was favored by ancient Egyptians as it represented youth,” she further explained.

“The golden and silver rings she wore, the wig she is wearing, and the painted wooden coffin in which she was interred all reflect her high socioeconomic status,” according to Saleem.