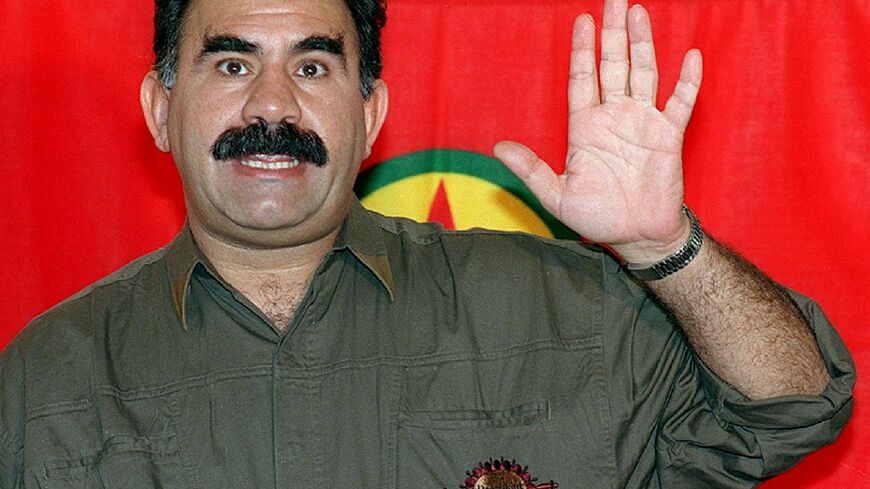

Ocalan: founder of the Kurdish militant PKK who authored its end

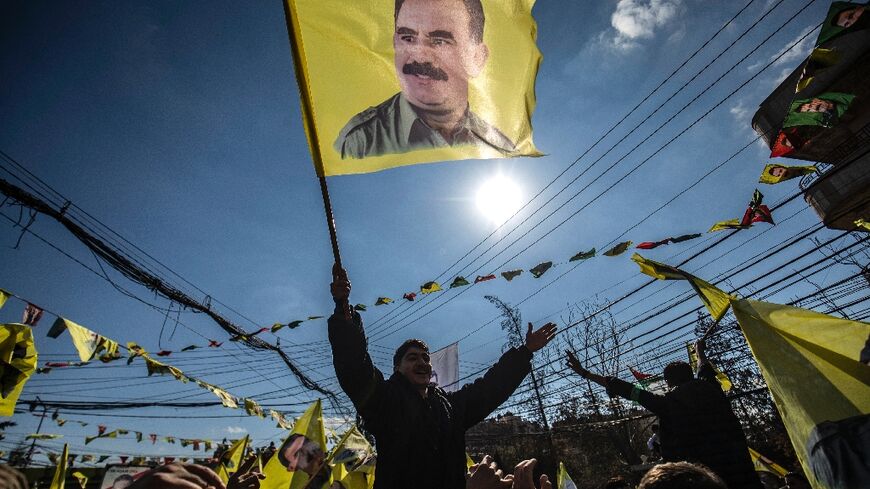

Abdullah Ocalan, the jailed founder of the militant Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), is an icon to many Kurds but a "terrorist" to many within wider Turkish society.

After a decades-long insurgency against the Turkish state that resulted in more than 40,000 deaths, the PKK on Friday will begin laying down its arms, two months after ending its armed struggle.

The move came after a historic call by Ocalan in February for his fighters to lay down their weapons and disband.

The 76-year-old is an inmate on the Imrali prison island near Istanbul, where he has been serving life in solitary confinement since 1999.

But since October, when Turkey moved to reset ties with the PKK, Ocalan has received regular visits by lawmakers from the pro-Kurdish opposition DEM party, as well as an increasing number of family visits.

And he is now leading efforts to switch from armed conflict to a democratic political struggle for the rights of Turkey's Kurdish minority.

"I believe in the power of politics and social peace, not weapons. And I call on you to put this principle into practice," he said in a video address on Wednesday.

- Public enemy number one -

For many Turks, Ocalan -- who founded the PKK in 1978 and embodies the Kurdish rebellion -- is public enemy number one.

A Marxist-inspired group, the PKK began an insurgency in 1984, demanding independence and later broader autonomy in Turkey's mostly Kurdish southeast.

It was quickly blacklisted as a "terror" organisation by Ankara, Washington, Brussels and many other Western countries and institutions.

Attitudes began shifting in October when ultra-nationalist MHP leader Devlet Bahceli, a close ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, offered Ocalan an olive branch if he would renounce violence.

Ocalan sent back a message saying he was indeed willing and was the only one who could shift the Kurdish question "from an arena of conflict and violence to one of law and politics".

Six weeks later, Syrian rebels overthrew ruler Bashar al-Assad, upending the regional balance of power and thrusting Turkey's complex relationship with the Kurds into the spotlight.

- From village life to militancy -

Seen as the world's largest stateless people, the Kurds were left without a country when the Ottoman Empire collapsed after World War I. Although most live in Turkey, where they make up around a fifth of the population, the Kurds are also spread across Syria, Iraq and Iran.

Ocalan was born into a mixed Turkish-Kurdish peasant family in Omerli, a village in Turkey's southeast on April 4, 1949. One of six siblings, his mother tongue is Turkish.

He became a left-wing activist while studying politics at university in Ankara and set up the PKK in 1978.

Six years later, Ocalan oversaw its shift to armed struggle, then spent years on the run.

He fled to Syria, from where he continued the struggle, until friction between Damascus and Ankara forced him on the run again in 1998.

Moving from Russia to Italy, then Greece in search of a haven, he ended up at the Greek consulate in Kenya, where US agents got wind of his presence and tipped off Ankara.

Turkish agents then snatched him in an operation fit for a Hollywood film on February 15, 1999.

Sentenced to death, he escaped the gallows when Turkey began abolishing capital punishment in 2002, living out the rest of his days in isolation on Imrali.

For many Kurds, he is a hero whom they refer to as "Apo" (uncle). But Turks often call him "bebek katili" (baby killer), for the PKK's ruthless tactics, which included bombing civilian targets.

- Jailed but still leading -

With Ocalan's arrest, Ankara thought it had decapitated the PKK.

But even from his cell, Ocalan continued to lead the group, ordering a ceasefire that lasted from 1999 until 2004.

In 2005, he ordered followers to renounce the idea of an independent Kurdish state and campaign for autonomy in their respective countries.

Tentative moves to resolve Turkey's "Kurdish problem" began in 2008 but made little headway.

Ocalan was soon involved in another round of unofficial talks in 2013 when Erdogan was prime minister.

But that collapsed in July 2015, sparking one of the deadliest chapters in the conflict and triggering a string of punishing Turkish military operations.

Although the violence eventually tailed off, there were no further efforts to resume dialogue until last year.

"The PKK movement, its pursuit of a separate state and its underlying strategy of war for national liberation has ended," Ocalan said on Wednesday in a speech that dismissed the idea of his own release as unimportant.

"He makes clear his own freedom has little importance, contradicting the conditions laid down by the PKK, which demanded his release so it could complete the process," Boris James, a French expert on Kurdish history, told AFP.

"He remains the leader, but not in any operational sense. He's positioning himself more as a guide for the movement."