PKK holds congress in response to Ocalan's call to end war with Turkey

The PKK announced that it had held a congress in Iraqi Kurdistan, most likely to decide on disbanding after its leader's call to end its insurgency.

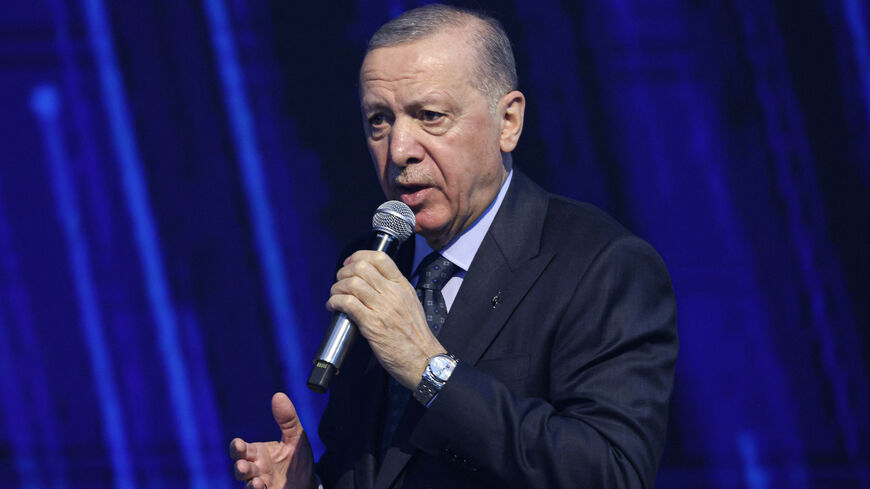

The outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) announced on Friday that it had held a long-awaited congress in response to a call by its imprisoned leader, Abdullah Ocalan, a move that will likely mark the end of the group’s four-decade-long armed campaign against the Turkish state and deliver a historic win for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The PKK said in a statement that the gathering had been held in the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan May 5-7 and that it would be sharing details of its deliberations with the public in the coming days.

On Feb. 27, Ocalan ordered the rebel army that he founded in the late 1970s — originally aimed at establishing an independent Kurdistan carved out of Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria — to end its fight, saying it had become redundant. Ocalan made the call following months of secret talks with Ankara, as first reported by Al-Monitor.

The PKK responded that it would obey Ocalan’s orders, and that his leadership remained uncontested, but insisted that he be present at the congress to direct the proceedings. Ankara refused to accept the condition, and Erdogan was said to be ready to shelve the initiative, forcing the PKK to change tack. The group is widely expected to announce its transition from an armed group to a political organization, a move additionally calculated to render moot its designation as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the European Union and the United States.

Erdogan, the first Turkish leader to authorize direct and sustained peace talks with the PKK, had not commented on the group’s announcement at the time of this article's publication.

Kurdish leaders hailed the news as historic and the start of a new era of peace.

“Today we are witnessing one of the most critical thresholds in Turkey’s recent history. This is not the end, it’s a new beginning,” Turkey’s largest pro-Kurdish party, DEM, said in a statement.

“Now the road to peace will start to be paved,” said DEM co-chair Pervin Buldan, who was part of a delegation carrying messages between Ocalan and the PKK’s top commanders in Iraqi Kurdistan. “Historic steps will be taken. Most likely expectations will be fulfilled. May it be auspicious for all.”

Buldan told the pro-PKK Mezopotamya news agency that “technical contact” between the rebels and Ocalan had likely been secured and that Erdogan would “imminently” make a statement on the PKK announcement.

Sources with close knowledge of the process said the announcement of the PKK's dissolution was likely to be made by Ocalan personally. Whether he will do so in a publicly aired video or via the DEM remains unknown, the sources said.

Opportunity and risks

The road ahead is likely to be bumpy amid a slew of unanswered questions about the PKK’s fate.

This is not the first time that the organization has announced an end to the war or to its own dissolution. It did so previously soon after Ocalan's captured in 1999, and again in 2003, only to reappear on the scene with its original name and to resume the war. At the same time, the PKK is not only a fighting force, but also a global network with murky business interests and millions of supporters in the diaspora.

What will happen to the estimated 5,000 fighters in Iraqi Kurdistan? How many would be eligible for amnesty? Will top commanders on Turkey’s most wanted terrorist list benefit? How will the Turkish public react?

And what about would-be saboteurs lurking in the background? On April 11, Buldan suffered injuries in a traffic accident in Rome, sparking speculation of an attempted assassination aimed at unraveling the peace initiative. Buldan said she found the speculation “inappropriate.”

In January 2013, just as Erdogan began a second round of peace talks with the PKK, three Kurdish female activists — including a former guerrilla commander, Sakine Cansiz — were murdered in Paris by a man said to have been on the payroll of rogue Turkish intelligence officers. The talks eventually collapsed in 2015 amid mutual recriminations.

Peace dividend

Turkey’s so-called deep state — an alliance of military officers and bureaucrats in the security services and the judiciary who made key policy decisions from behind the scenes — long used the Kurdish insurgency to justify the brutal repression of the country’s large Kurdish minority and to criminalize their demands for political and cultural rights on the grounds that they threatened the country’s territorial integrity. At the same time, this ensured continued military tutelage, with the army receiving a lion’s share of the country’s budget.

After rising to power in 2002, Erdogan doggedly chipped away at the army’s power and reached out to the Kurds as he enacted a raft of unprecedented reforms raising hopes that Turkey was on the way to becoming a full democracy. The European Union was so impressed it launched (now frozen) membership talks with Turkey in 2005.

Erdogan eventually succeeded in defanging the generals after protracted battles, including the failed coup attempt in 2016. Today’s announcement could have been viewed as his crowning achievement in securing the future of Turkish democracy, one that may have been harder to achieve had his far-right nationalist partner, Devlet Bahceli, not helped legitimize the initiative by becoming its biggest cheerleader.

Erdogan’s descent into full blown authoritarianism over the past decade has, however, cast a pall. Even as Kurds across the region hail the PKK’s decision to disavow violence against Turkey, Erdogan’s opponents, notably from the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), say the current initiative cannot lead to democratization.

Pressure has steadily been building on the CHP since it wrested a string of municipalities, including Istanbul and Ankara, from Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2019 local elections. Kurdish support helped sway the outcome in the CHP’s favor in an alliance that also met with success in 2024, when the CHP defeated the AKP nationally for the first time.

Istanbul’s CHP mayor, Ekrem Imamoglu, a key architect of the compact with the DEM, has emerged as the one man who can easily beat Erdogan in presidential elections, according to multiple polls. Authorities arrested Imamoglu on March 19 on thinly evidenced corruption charges, sparking nationwide protests amid widespread claims that Erdogan gave the order in a bid to block his path.

Divide and rule

The Turkish president’s latest attempt at securing a peace deal with the Kurds is also widely seen as part of an effort to drive a wedge between the CHP and DEM and to win the latter’s support for constitutional changes that would allow him to run for, and win, a third presidential term in elections scheduled for 2028.

The government branded the peace initiative Terror Free Turkey and claims that it was launched to protect the country from regional instability and violence. Unlike previous efforts, this time the government has turned the process on its head, saying it will not consider any steps until the PKK disarms and disbands.

Still, sources with close knowledge of the deliberations say Ocalan was promised improved living conditions. In addition, around 50,000 political prisoners, many of them ill and older Kurds, are to be freed under the terms of a new amnesty package that will be submitted to the Ministry of Justice for review and then to the parliament, where the government and its nationalist allies command a sufficient majority to pass it. A second package would see other high-profile prisoners released, including Turkey’s most popular Kurdish politician, Selahattin Demirtas, who has been languishing in jail since 2016 on specious terrorism charges.

The most immediate beneficiaries, however, will be the Kurds of northeastern Syria. Since Ocalan’s call, Turkey’s attacks against the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces have all but ceased, and Ankara stood by as its ally in Syria, President Ahmad al-Sharaa, signed a landmark deal on March 10 with SDF commander in chief Mazlum Kobane.

Bayar Dosky, an Iraqi Kurdish academic, said Ocalan and the PKK had made the strategic decision to forgo big gains in Turkey to salvage those in northeastern Syria. “The mother sacrificed herself for the baby,” Dosky told Al-Monitor.

Roj Girasun, co-founder of RAWEST, a research and polling outfit based in Diyarbakir, the Kurds’ unofficial capital in Turkey’s Kurdish-majority southeast, agreed.

“The main issue is that the potential for [renewed] conflict between Turkey and Kurds living on the other side of the border has largely subsided and that Turkey has de facto accepted autonomy [for Syria’s Kurds],” Girasun told Al-Monitor. “More broadly, the Kurds’ biggest win is that they have been relieved of the burden of an outdated method of seeking their rights, of using violent means to achieve democratic gains.”

This developing story has been updated.