Suck my walls: One woman’s archive of Turkey’s street art

From the Marmaray underpasses to the erased slogans in Gezi Park, Irem Guler has spent two decades documenting Turkey’s graffiti and street art, tracing how it is made, claimed and erased.

You expect someone with a handle like “Suck My Walls” on Instagram to be abrasive, perhaps performatively confrontational and a little too pleased with provocation. What you do not expect is Irem Guler: a soft-spoken, reflective and academically inclined observer of Turkey’s graffiti history.

“The handle came from my flaneuse phase, when I was studying at the French high school Notre Dame de Sion in Istanbul,” Guler explained, laughing. Back then, she wandered the city without a plan, absorbing rather than documenting. The handle stuck, often inviting commentary and surprise when people met the person behind it. “It does sound like it belongs to a tough guy,” she said, “someone who addresses you as ‘bro,’ like many graffiti writers.” Today, the account has become one of the most comprehensive visual records of graffiti and street art in Turkey, with over 7,000 followers worldwide.

In the early 2000s, before she had the vocabulary for what she was seeing, a friend invited her to watch someone paint a typographic tag. She went home, tried to copy it on paper, failed, and understood that the failure mattered. “I realized the beauty and the complexity of what I could not imitate,” she told Al-Monitor. “So I started photographing instead.” With an early phone camera and a habit of long walks, she learned to hunt for murals where the city was most exposed — underpasses, tunnel mouths, transport arteries. Graffiti trained her eye to read the city spatially.

That way of looking was later sharpened by training. Educated in archaeology and drawn to sociology and philosophy, Guler approached walls as layered texts rather than isolated images. “I am interested in what touches what,” she said. “Which moment hits which surface, and why.” The Tumblr account she opened in her 20s carried the brashness of youth. What followed was discipline. She estimated that she had since taken more than 100,000 photographs across Istanbul, Ankara, Antalya and other Turkish cities. There were no captions that romanticized decay and no attempts to crown heroes. The gesture was closer to testimony than curation: This was here. Someone risked making it because they had something to say, even if it was only to say they existed.

We met in Suadiye, a residential neighborhood on Istanbul’s Anatolian side, just by the Marmaray line, the commuter rail connecting the city’s European and Asian sides under the Bosphorus. We walked along the tracks, surrounded by concrete walls covered in overlapping names and half-finished experiments. Guler called this stretch a scratchpad. “It is one of the rare places where the rules of painting over someone else’s work are looser,” she explained. “Writers test styles here — repainting, collaborating, layering and pushing forms rather than staking claims in the territory.” Elsewhere, painting over another artist’s work is a serious violation. “That is how you get an old-fashioned street fight,” she said, only half-joking.

Tehran-Istanbul-Beirut, a group of international artists known for their teasing style. (Courtesy of İrem Guler)

Street art in Turkey, Guler noted, did not emerge in isolation. It rose alongside hip-hop culture, with rap acting as a carrier of language, posture and attitude.

It did not take root easily, either. In the 1980s, Tunc “Turbo” Dindas, widely regarded as a pioneer of Turkish graffiti, was detained after police claimed one of his tags resembled a hammer and sickle. “So I was taken before a judge for communist propaganda,” he told Al-Monitor, referring to laws shaped by the military era. “Fortunately, I was underage, and my sentence was converted into a fine.”

Moving mainstream

Turbo’s work later entered galleries, biennials and commercial campaigns. His participation in the Istanbul Biennial in 2005 is often cited as a turning point that allowed underground aesthetics to move from margins into the mainstream. By the early 2010s, murals appeared in festivals and municipal programs. By the time of the Gezi Park protests in 2013 — mass demonstrations that began over the redevelopment of a central Istanbul park and evolved into nationwide protests over rights and governance — walls became sites of collective expression, particularly in Beyoglu, Taksim and Karakoy, long-established corridors of graffiti activity.

“The works during Gezi were not all beautiful, nor refined,” Guler said, noting how quickly people had to act to avoid detention. “But they were incredibly expressive.”

She was careful not to romanticize Gezi as an artistic golden age. Most works were temporary, technically crude and swiftly erased. What mattered was initiative: pens, stencils, cardboard signs and improvised slogans. “It was not about skill,” she said. “It was about saying something, anywhere.”

The effect lingered. In 2014, Pera Museum, not known as a bastion of avant-gardism, held an exhibition on graffiti and street art called “Language of the Wall.” Graffiti typography migrated further into advertising, sports venues and brand campaigns. An underground language was absorbed, flattened and resold.

Subcultures, Guler said, are always pulled upward once they begin interrupting thought.

Her archive captures these contradictions without adjudicating them: political works that vanished within minutes; decorative ones that lingered for years; rising spray-paint prices that push younger artists toward stencils and stickers; neighborhoods sustaining different ethics and risks. Bourgeois-bohemian Kadikoy, with its galleries and cafes, stands worlds apart from working-class Avcilar, where graffiti often functions as an initiation rather than art. Each has its own grammar, said Guler.

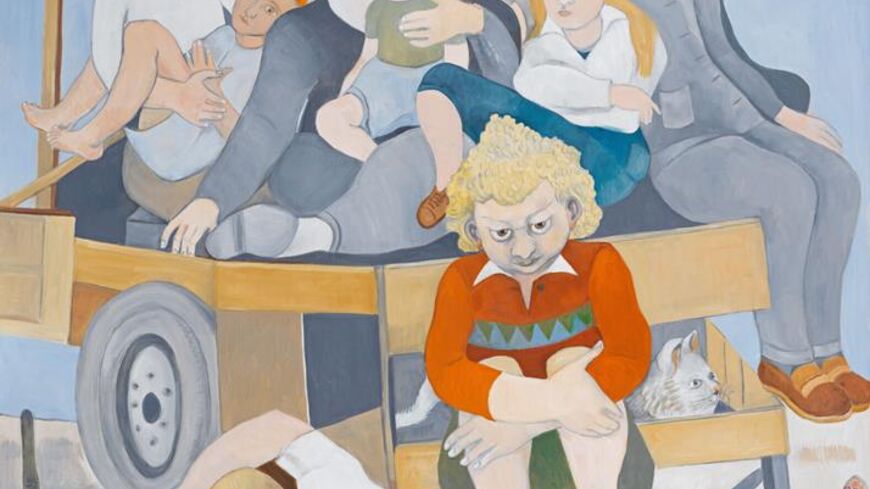

Rash combines graphic forms with human figures. (Courtesy of İrem Guler)

Artists and signatures

As we walked along the wall of Suadiye train station, Guler spoke of works and artists the way a seasoned musician might speak of composers, pointing out signatures and styles with quiet affection. “You always see the red cockroach in the works of Canavar,” she said. She gestured to another piece. “This is by Rakun, a graffiti artist who died last year. Other artists are careful not to paint over his work,” she added, describing the wrinkled, almost alien faces that marked his style. Nearby, a mural signed “Tehran-Istanbul-Beirut” belonged to an international collective known for cartoon-like figures and cross-border collaborations.

Artists such as Turbo, Meck, Canavar, Cins, Rigor Mortis, Reach Geblo, Mr. Hure, Leo and Esk Reyn have shaped Turkey’s visual street language, spanning old-school graffiti, politically charged interventions and large-scale murals. Some remain fiercely anti-commercial; others navigated commissions and festivals. Alongside individuals, platforms such as MuralEst have played key roles in expanding mural practices into broader public visibility.

What united them, Guler suggested, is not style, but presence: the insistence on being seen, however briefly.

Gender left its trace as well. Graffiti has remained heavily male-dominated, though more and more women are present, sometimes prominent, and often isolated. Younger women, she noted, were now forming microcommunities of their own, entering the street without disguising either their work or their identities. Visibility, again, is the act.

Asked what she looked for now, after two decades of walking, watching and leading street art walks, Guler paused. “Courage,” she said. Not compositional perfection, not cleverness, not permanence, but "the courage to stop, to mark, to speak in a space that does not belong to you."

In a country where public space is increasingly regulated, protest is criminalized and visual dissent is erased almost as quickly as it appears, Guler’s archive functions as more than cultural memory. It is a record of who spoke, where they spoke and how long they were allowed to remain visible before power intervened.

Irem Guler also leads street art walks, extending this practice of walking, looking and contextualizing into a shared experience. DM on Instagram @suckmywalls.