Copts, Nubians, and Berbers fight to keep Egypt’s endangered languages alive

Far from Cairo’s bustle, Egypt’s minority communities are fighting to preserve their ancient languages against the tide of Arabization and cultural loss.

CAIRO — Far from Egypt’s busy capital, minority communities are struggling to preserve and protect their unique culture and languages from extinction.

With a population of over 118 million, Egypt is home to distinct minorities with their own traditions, beliefs and languages that have enriched Egypt’s cultural identity for millennia. Some of these languages are on the brink of extinction, however, and some of their speakers are refusing to let them vanish. They are working online and offline to keep their indigenous languages alive.

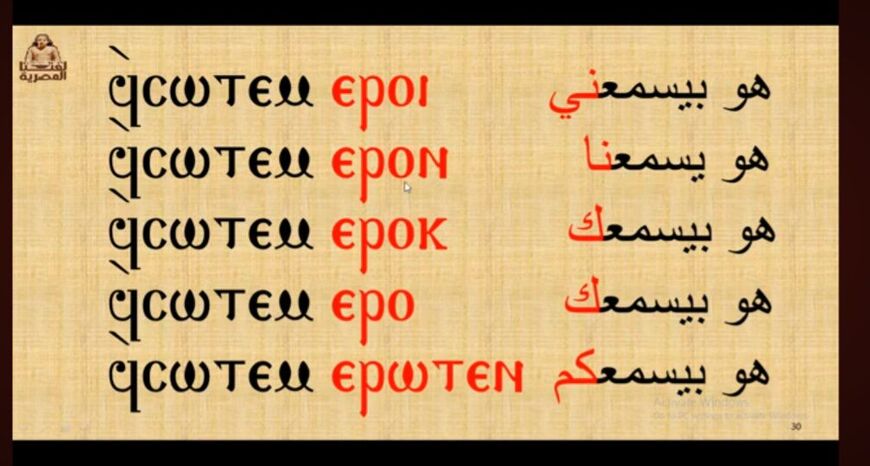

Coptic, last link to ancient Egyptians' language

Amr al-Sharkawy is a Coptic language instructor at the Franciscan Cultural Center for Coptic Studies in Cairo. Born in a small village in the Muslim-majority el-Menoufia governorate in northern Egypt, Sharkawy became fascinated with the Coptic language during his studies at the Faculty of Arts of Menofia University and decided to study it and then teach it. As a Muslim living in a conservative society, he faced disapproval from his family.

“The professor of history during my second year in university was Habil Fahmy Abdel Malek. He is a Christian Orthodox who used to use Coptic words and phrases during lectures. I was inspired by the language and decided to specialize in it,” Sharkawy told Al-Monitor.

“Some people asked me, ‘Why don't you study Arabic and the holy Quran rather than Coptic?’ But the Coptic language has a special value because it is the last form of the ancient Egyptian language that people spoke before they started using the Arabic language,” he explained. Sharkawy, a PhD candidate at the Institute of Coptic Research and Studies at Alexandria University, also teaches the language online and shares knowledge on Facebook groups dedicated to teaching the language.

Of all the dialects of Coptic, the best known is the standard dialect, Sahidic. It was used by Saint Shenouda the Archimandrite, who lived in Sohag in the fourth century AC.

“The oldest papyrus found written in Coptic language is the Heidelberg Papyrus 414. It dates back to the mid-third century before Christ,” said Sharkawy.

The estimated number of Coptic people in Egypt is 15 million, according to Pope Tawadros II, the head of the country’s Coptic Orthodox Church. However, the number of Coptic speakers is smaller. Coptic is mainly used in churches and in small villages in Egypt’s south. But the language is currently gaining popularity outside the religious context.

“Year after year, the number of specialists and students of Coptic language is increasing, and so are centers teaching the language,” Sharkawy noted.

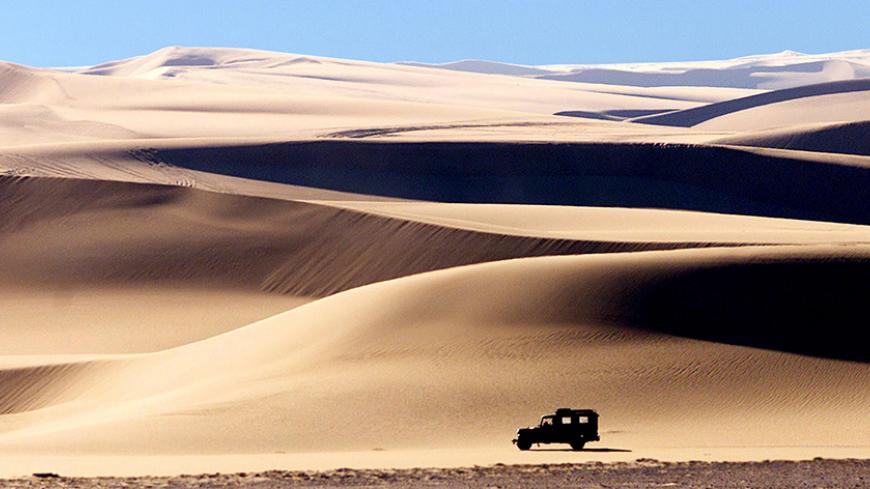

Fight to save endangered Nubian, Berber languages

Another ancient tongue declining in Egypt is a language in the Nubian family. There are no official figures of the Nubian population in Egypt, but some human rights groups, including the Minority Rights Group, suggest there could be as many as 3 to 5 million Nubians. Much of the older generation of Aswan governorate in the south still speaks the local Nubian language, and it is actively used in daily life in Nubian villages like Gharb Soheil, Heisa and Anakato, which see heavy tourism throughout the year.

However, many young Nubians don't speak the local Nubian language either because they left the region at an early age or prefer Arabic as it opens more job opportunities for them.

Ahmed Essa, a Nubian poet in his mid-60s, has been offering online lessons on YouTube for over 15 years. “To keep our language alive, we teach it online, post about it on social media and sing our Nubian songs together,” he told Al-Monitor.

Most of Essa's students are young, but some are older members who left their Nubian communities at young ages.

Essa said he is often asked by young people, "Why should we learn Nubian and how will it benefit us?" He answers, "In fact, language is the identity that differentiates a person from another.”

Fathy Gayer, a 65-year-old independent researcher of Nubian culture, created the online Nubian Forum for Language and Heritage in 2020. On the platform, more than 1,200 members share videos, photos and posts about language and culture.

“The goal of the forum is to preserve the Nubian language, which is the vessel for Nubian heritage, especially with the dominance and spread of Arabic among new generations. We fear the loss of identity and human heritage,” Gayer told Al-Monitor.

“I’m concerned about the future of the language, but we are doing our best. In a short period of time, we have been able to bring Nubian expats around the world together through this forum. We have begun to communicate, read and write in our language. This makes me hope that new generations can develop the idea we started,” he explained.

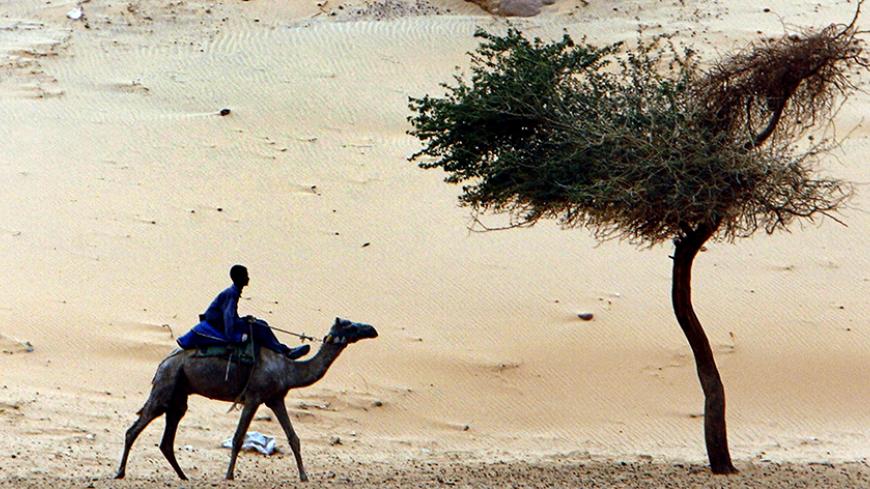

The Berber languages, or Amazigh as they are known within their communities, also face the same threat. The local one, Siwi, is spoken by a small community in the Siwa Oasis in Egypt's Western Desert, which has an estimated Berber population of 40,000 people. For Berbers, transmitting the language is vital for the survival of their culture.

Koila Agneby, a young Berber who was not formally educated but was taught by the elders of his community, decided to create online content about the Berber culture and language on Facebook and YouTube.

Agneby told Al-Monitor, “Preserving our culture is important. For over 15 years, people from other governorates have come to Siwa to live and start families. Those people brought their own cultures and [speech]. They marry into our community and teach their children colloquial Egyptian Arabic. So the community started to change.”

For him, Berbers are very different from Egyptians in terms of culture, clothing, cuisine and traditions, such as customs for weddings and funerals.

“We teach our children that we are Berbers. We usually don’t let our children mix with other Arab people in order not to influence their language or culture,” he said.

Amani al-Washahi, a representative of the Amazigh people of Egypt at the World Amazigh Congress, believes that the Berber language and culture is in danger.

“Amazigh culture in Egypt is currently at risk under fierce Arab acculturation,” she told Al-Monitor.

According to Washahi, some commercial projects such as resorts and cafes have raised concerns among members of the Amazigh community, who fear these developments will threaten their cultural heritage.

Washahi suggests that Egyptian authorities offer courses for the Amazigh language in cultural centers in Siwa Oasis to help in preserving the culture. “Unfortunately, the Amazigh of Egypt only speak the language. They do not write or read it, but they are very keen to learn it,” she reflected.