Healing through art: Syria’s artists seek to unite a fractured nation

From Damascus to Idlib, a new generation of Syrian artists is reclaiming public space and rebuilding cultural life through contemporary art.

DAMASCUS — In a dimly lit hall in Idlib, visitors are first met with their own reflections. A mirror embedded in a video installation captures each person’s image as sound swells around them. The work, Hala Nahar’s “New Birth,” refuses passive viewing. It comes alive only when the audience steps inside. People lean in, hesitate, then stay, watching themselves become part of the artwork.

"New Birth" is one of dozens of installations traveling across Syria as part of “Path 2,” a multicity exhibition by the Madad Art Foundation that’s bringing contemporary art — and a fragile sense of togetherness — back into public spaces that have been scarred by war.

The initiative spans five provinces — Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Latakia and Idlib — and deliberately occupies public, symbolic and long-unused spaces: train stations, cultural centers, derelict buildings and courtyards turned into open galleries. Madad’s curatorial bet is simple and bold: Take contemporary art to the people, let communities co-create the experience and rebuild cultural life in the process.

"Transition" by Syrian artist Ali Majar at the "Path 2" exhibition in Idlib. (Image courtesy of Orabi)

“As an artist, visiting and exhibiting in Idlib was a truly unique experience, one many people didn’t expect,” Nahar tells Al-Monitor.

The sensibility is less about spectacle than it is about contact. Idlib’s audiences, Nahar recalls, were initially shy. “People described my work as strange, yet deeply moving.”

Personal paths, shared journeys

Across the country, young artists echo the move from private reflection to public connection. Noor Deeb, 26, arrives at "Path" with a clear refusal to sentimentalize the present.

“For me, 'path' no longer means a clear journey forward; it’s a map constantly redrawn by forces beyond our control. It’s not a road you walk, but a maze you’re placed inside,” she avers. “My work, 'The Luxury of Choice,' reflects our collective Syrian journey — a decade where even the simplest choices, like to live or to stay, became impossible. The three wire crows represent annihilation, silence and exile.”

Fares Aldeen Baakar, 21, explores the psychology of pressure and rupture. His installation suspends 10 ropes midair, nine frayed to the point of nearly snapping, the final one intact.

“'Path' is a big word, one that can mean something different to every person,” Baakar says. “For me, it shaped my journey with this artwork. I wanted to release an emotion, to step out of a 'path' I felt trapped in for a long time.”

“In the installation, each passage between the ropes becomes tighter, until it finally closes off.”

Two sisters, Razan and Malaz, stand together in front of their collaborative work, "Hidden Dimension." They speak as one creative mind — Orabi — a shared artistic identity that explores perception, imagination and the spaces where inner and outer worlds meet.

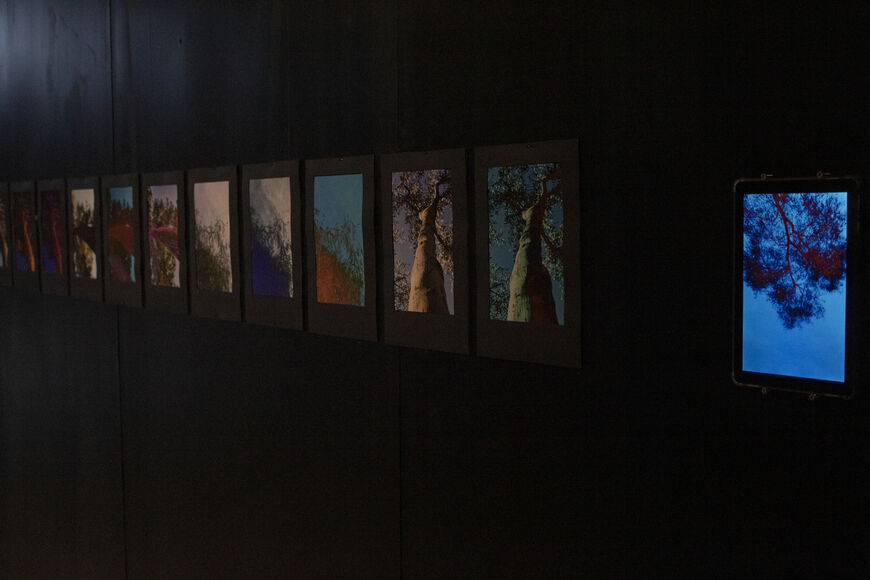

“Hidden Dimension” by the artist duo known as Orabi at the "Path 2" exhibition in Idlib. (Image courtesy of Orabi)

“In 'Path' we wanted to experience what it means to make peace between reality and fiction,” Orabi told Al-Monitor. “People often think that fiction and reality are separate, but they’re actually rooted in each other.”

They recall a philosopher’s idea that shaped their vision: “Fiction isn’t detached from reality — it grows from it.” That idea, they explain, guided the evolution of their ongoing project.

“We asked viewers to enter our mind space, to see a colored tree that doesn’t exist in nature, or imagine a hidden place to keep the heart outside the body.”

"Art can travel where people can’t, and it reconnects us beyond politics or division.”

Stitching what's torn

Meanwhile, art designer Judy Chakhachirou — one of the exhibition's lead designers — explores the same themes with a literal needle, threading rupture into repair. “I never thought 'Path' would mean so much,” she told Al-Monitor.

“Personally, it’s the road I chose, the one that shaped me. Artistically, it’s where my story crosses with others.”

What began as something private became something shared: “I saw my emotions reflected in others — it felt like standing before a two-way mirror.”

In her piece, the needle stops being a tool and becomes the message: “It can cut and expose, but it can also stitch and repair.” Watching the show travel between provinces confirmed the stakes.

That belief — that art can move even where people cannot — is a through line of "Path 2." In Aleppo, Madad teamed up with the city’s grassroots art collective, Mashrou By Default, an art production hub that has been reimagining battered buildings as ad hoc cultural venues.

“Syrian Reservoir” at the "Path 2" exhibition in Idlib. (Image courtesy of Orabi)

“Mashrou By Default is an Aleppo-based cultural hub reshaping the city’s art scene,” says Yaman Najeh, from the collective. “We produce exhibitions and cultural events from the ground up, developing the themes, artworks and ideas ourselves.”

“We often choose disused or damaged buildings and rebuild them into creative spaces. It’s about giving Aleppo’s artists a platform and reviving places that once felt forgotten.”

Participants consistently describe the Madad-Mashrou By Default partnership as one of the strongest cultural collaborations operating inside the country this year — evidence that institutional experience and community-based initiative can meet in the middle, and quickly.

New generations, new voices

For Sana Al Ikhlassi, 23, the exhibition's timing felt like a personal milestone.

“For me personally, 'Path' was a big challenge because it coincided exactly with my graduation project,” says the Aleppo-based artist. “As an artist, it was a completely new experience; it took me beyond the usual world of paintings."

“My work reflects everyone — it speaks to the collective experience,” she added, describing a piece centered on forgiveness. “Forgiveness is something that never really ends, so there’s no fixed place or time for my work. It’s something that will stay tied to my memory for life.”

The "Path" platform offers a way to name social fractures without surrendering to them, according to Jad Tatou, who explains to Al-Monitor that "Path" was more than an exhibition.

“'Path' is a bridge reconnecting Syrians across our divisions. My work speaks about the gaps within society and how these fractures shape our personal and collective journeys.”

Dina Al-Ghafari, 23, brings a different perspective: the unruly churn of grief and anger, and the discipline it takes to sit with both. Participating in the Hom’s exhibit, she told Al-Monitor, “I think we’re all on different journeys but walking the same path. Most of us are just trying to survive, to find work and support our families,” she said. “My piece began as a way to understand my own anger — why I felt the need to destroy my own work. I wanted to know if others feel that too.”

“This work is about where I’ve been stuck — a year marked by loss and grief that’s reshaped how I see everything. Art helped me heal."

If these artists hold a mirror to the present, the institution behind the platform has been busy carving out a cultural map that didn’t exist. The Madad Art Foundation, founded by Buthayna Ali — a respected artist, teacher and mentor who died recently — has quietly become one of the country’s most dependable drivers of contemporary art.

Toward the end of an evening in Idlib, a small crowd lingers before "New Birth." A boy stands at the threshold, then steps forward until the mirror frames his face. For a long moment, he doesn’t move. Around him the sound rises and falls. The hall is quiet, alive. Across five provinces, versions of that moment are now repeating.

“Especially now, with all that’s happening in Syria, art lets us connect without fear or limits,” Orabi say. “It reminds us how different and yet how deeply similar we all are — whether in Damascus, Homs, Aleppo, Idlib or Latakia. It’s all part of us.”