Hezbollah still dominant among Lebanon's Shiite, but ground is shifting

Two notable trends are emerging within Lebanon's Shiite community: growing rejection of geopoliticization, alongside continued loyalty to the resistance legacy despite mounting concerns over its consequences.

BEIRUT — The 2024 war between Hezbollah and Israel plunged Lebanon’s Shiite population into deep social, political and economic crises. The conflict scarred thousands of families, many of whom lost relatives — whether civilians or combatants — along with homes and entire village communities, particularly in the southern border region of Lebanon.

Some international institutions and governments have proposed various paths toward a “post-Hezbollah Lebanon.” These include creating a demilitarized economic zone in southern Lebanon’s border area, a proposal advanced by US President Donald Trump; enforcing Hezbollah’s disarmament through the Lebanese army; and pursuing full normalization between Lebanon and Israel.

As these proposals emerge, Israel continues to launch airstrikes into southern Lebanon, despite the November 2024 ceasefire, to increase pressure on Hezbollah.

Putting aside the unrealistic nature of these proposals, there is virtually no discussion among institutions and governments in North America and Western Europe of the desires of Lebanon’s Shiite population — the biggest target of the war — as few leaders can speak for them, despite the dominance of Hezbollah and the Amal Movement over the Shiite political scene after the civil war that ended in 1990.

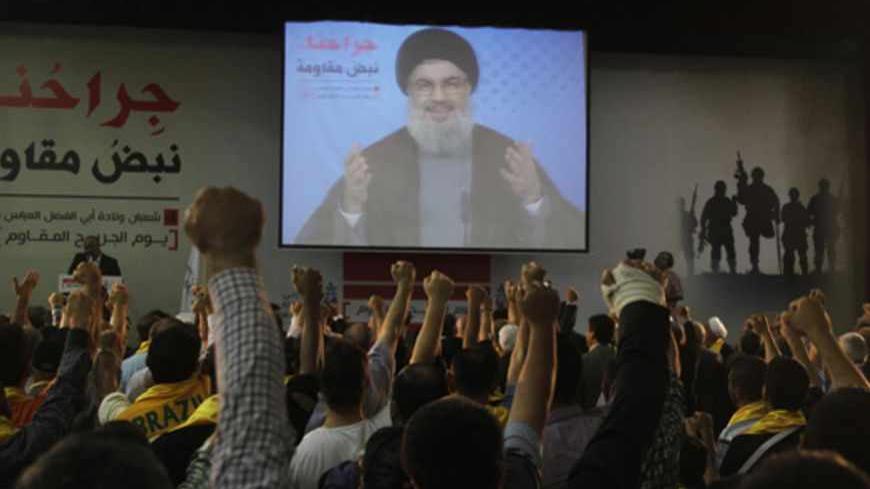

Historically, the community was represented by a number of powerful families, accompanied by voluntary involvement in several leftist and nationalist parties in the latter half of the 20th century. Following Musa al-Sadr’s arrival in 1959 and the establishment of Amal in 1974, the Shiite community’s political activity became increasingly defined by sectarian and revolutionary religious currents, especially after Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Parliament speaker Nabih Berri — a long-term Hezbollah ally — is attempting to create an impossible balance between two domestic and regional sensitivities: buying Hezbollah time to restructure, and maintaining Lebanon’s relationship with its US and Arab partners.

Against this backdrop, polls conducted in the past few years point to two notable trends among the Shiite community: first, increased rejection of geopoliticization; and second, loyalty to the resistance legacy, despite concerns over the outcome.

Rejecting geopoliticization: Leaning inward

An initial poll of 400 people released on Oct. 30, 2023, by the pro-Hezbollah Consultative Center for Studies and Documentation displays insightful indicators. Despite the Shiite population’s overwhelming support for media-based and diplomatic pressure on Israel during the Gaza war, 49.2% opposed full-scale intervention in the conflict.

This poll was conducted at a time when Hezbollah had not yet accumulated significant losses compared to its situation a year later. Amid the initial phase of the war in 2023, a majority of Lebanese across sects still openly prioritized domestic reform over engaging in war.

According to a 2024 Arab Barometer study, overall trust in Hezbollah among Lebanese citizens stood at roughly 30%, but this support is almost entirely concentrated within the Shiite community. About 85% of Shiite respondents reported having “quite a bit” or “a great deal” of trust in Hezbollah, while trust among other sects remained minimal — under 10% among Sunnis (9%), Druze (9%), and Christians (6%). In addition, the study estimates that around 22% of Lebanese Shiites did not think Hezbollah’s involvement in regional politics was generally a positive factor.

Al-Monitor spoke with "Ali" in the Bekaa near the Syrian border. He preferred not to reveal his full name for safety reasons. Ali has maintained his sympathies for Berri, given the sense of threat from an antagonistic new order in Syria.

“Hezbollah shouldn’t have supported the Palestinian Hamas group in the Gaza Strip,” Ali said, lamenting the latter’s recklessness in accounting for the repercussions of its Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel.

Many like him today are primarily concerned with acquiring tangible resources for reconstruction in Lebanon.

By April 2025, a poll of 1,500 respondents released by Information International and Annahar found that over half of Lebanon’s Shiites (50.7%) viewed Iran, Hezbollah’s main backer, negatively. This perception stems from a belief that Iran “sold out” Hezbollah’s late secretary-general, Hassan Nasrallah — who was killed by Israel in a strike in Beirut on Sept. 27, 2024 — to preserve elements of its regional standing. Nasrallah’s assassination came nearly a year after heavy cross-border exchanges between Hezbollah and Israel escalated into a full-blown war in September 2024, one of the deadliest conflicts Lebanon has faced in the past 40 years.

Over 4,000 people, including civilians and Hezbollah members, were killed between Oct. 8, 2023, and Nov. 27, 2024, when a US-brokered ceasefire entered into force.

Ambiguous loyalty to the “resistance legacy”

The World Bank estimates that economic losses from the Israel-Hezbollah war amount to a potential total of $14 billion, with $11 billion needed for reconstruction. Hezbollah’s war with Israel reduced the influence of the group and its allies over the security deep state, reinforcing a sense of “political defeat” among an already victimized support base.

Given the significant material and political losses, Hezbollah’s support base remains largely on the defensive in the context of a major existential shock. In the region’s highly sectarian political environment, the group’s supporters are wary of empowering their opponents in both Lebanon and Syria, particularly those who have historically opposed Hezbollah’s political hegemony. Furthermore, Nasrallah’s charismatic presence and the nostalgia associated with him continue to motivate attachment to conceptions of “national liberation” and “resistance.”

This is supported by polling data conducted by Gallup between June and July 2025, demonstrating that only 27% of Shiites as of December 2025 believe in the need for a state monopoly on arms.

Pro-Hezbollah analysts regularly posit that the Lebanese Army is constrained by a deliberate US plan to weaken its infrastructure. For them, maintaining a balance of power with Israel requires Hezbollah’s militarized institutional presence.

However, the Gallup poll also shows that 98% of Shiites still have confidence in the country’s military, showcasing a contradictory and ambiguous stance informed by a dual appreciation for both “resistance” and “army.”

‘Shiite opposition’ to Hezbollah: Is a revision possible?

Hezbollah often evades responsibility by invoking sectarian rhetoric: Those who challenge its narrative are frequently portrayed as indifferent to the suffering of Lebanese Shiites.

Nevertheless, Shiite opposition to Hezbollah’s war narrative exists, focusing on revising past military maneuvers, strengthening trust in the state and emphasizing a permanent truce with Israel. Some dissidents within the sect, such as journalist Mohammad Barakat, emphasize their Lebanese and Arab identity over Iranian alignment, advocating commitment to state sovereignty; stronger Arab relations, including with Saudi Arabia; adherence to the Arab Peace Initiative; and cooperation with the “new Syria” under Ahmed al-Sharaa.

Dissidents also include renewed liberal and leftist currents that oppose Hezbollah and Lebanon’s sectarian-based system more broadly. Ali Mourad, a parliamentary candidate who ran in southern Lebanon’s Bint Jbeil district in 2022, stressed the need for state-building based on equality among all citizens, away from displays of arms, domination and surplus power, as part of a broader process of establishing a secular democratic system.

These diverse currents illustrate the range of visions challenging Hezbollah’s monopolization of the popular narrative.

Nevertheless, the 2025 municipal elections in which Hezbollah-backed candidates secured several seats demonstrated that opposition to Hezbollah within southern Lebanon and the Bekaa — both strongholds of the group — remains weak, disorganized and precarious. While municipal work is tightly connected to the local relevance of large families and the initiative of individual officials, it also serves as a reminder of Hezbollah’s robustness and grassroots presence.

A sectarian-based opposition is unlikely to challenge Hezbollah and its allies within the Shiite community. This highlights the need for a broader, cross-sectarian approach that goes beyond Hezbollah, including but not restricted to necessary and urgent economic and electoral reform.