Turkey’s graphic-novel culture blossoms in face of censorship

A fragile but growing ecosystem of artists, editors and cross-border collaborations is reshaping Turkey’s graphic-novel landscape under tight political and economic constraints.

Turgut Yuksel’s hero in the graphic novel “Seven Deadly Days” is a young graphic designer whose dreary routine is instantly recognizable to a whole generation of Turkish white-collar workers. He works in one of Istanbul’s chic plazas, wakes before dawn for a three-hour commute because his salary pushes him far beyond the city center, accepts unpaid overtime and the boss’s shady Photoshop requests as part of the job description and watches colleagues disappear in the weekly cycle of layoffs.

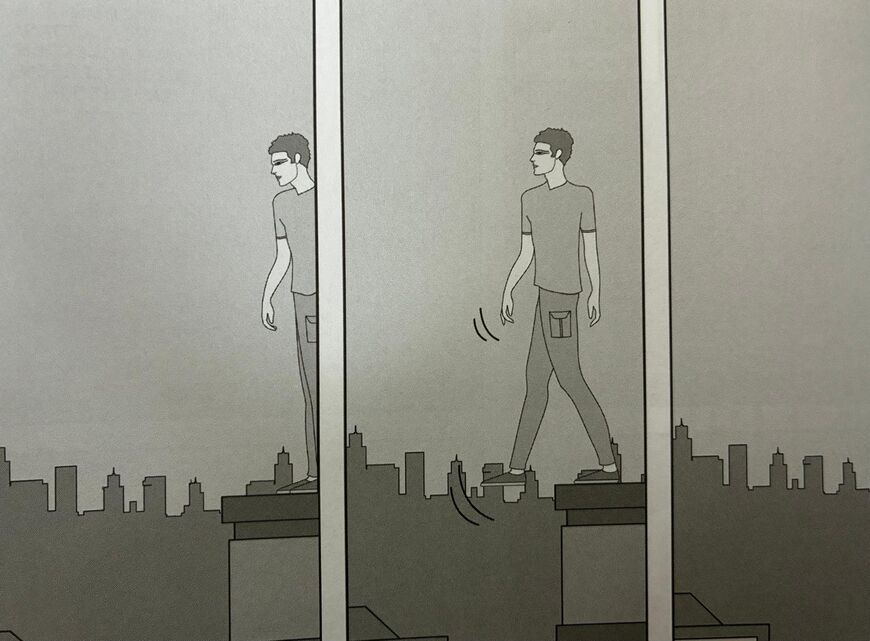

Yuksel spent years in the same corridors and on the same buses. “Seeing the weary faces of fellow commuters day in and day out may be the start of ‘Seven Deadly Days,’” he told Al-Monitor. His clean, tightly framed, two-dimensional panels with no depth intensify the claustrophobia of the job-home-bus triangle.

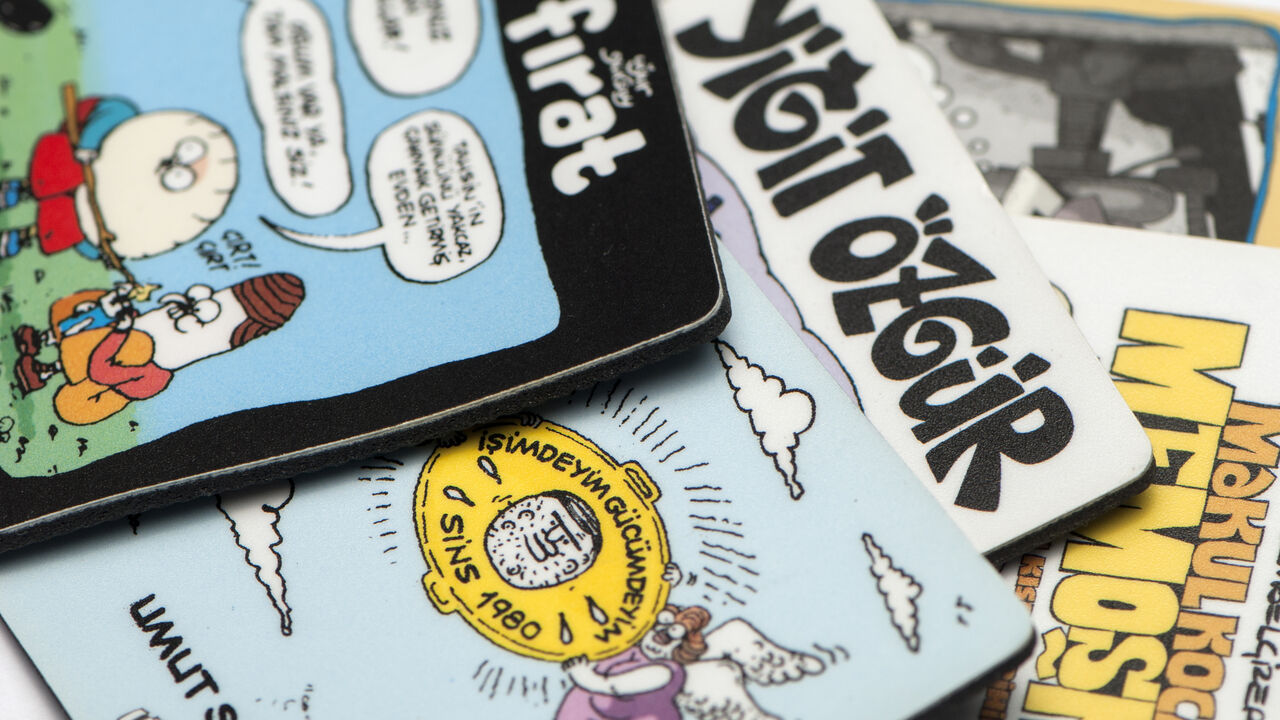

“Seven Deadly Days” is emblematic of a slow shift in Turkey’s graphic-novel landscape. Imported titles and manga still dominate shelves, yet books like Yuksel’s suggest that Turkish artists are beginning to use sequential art to explore precarity, migration, gender and everyday survival, themes once left to film, memoir and Turkey’s satirical weeklies.

“Turkey has world-class illustrators,” said Yuksel, who once drew a popular strip for Radikal, the influential newspaper of the 1990s and 2000s. “We also had great humor magazines for decades, such as Girgir, Penguen or Uykusuz. They shut down one after another, and those who remain, such as Leman, struggle under censorship and financial difficulties.”

True to form, Yuksel’s own work straddles the fantastical and the political. He created a digital weekly, “Brave New Pigya,” set in an imaginary country of injustice, nepotism and creeping authoritarianism, that later became a graphic novel. He has published 22 books, including one co-written with social scientist Tanil Bora on soccer culture. But producing long-form work remains a luxury.

“'Seven Deadly Days' took me a year,” he said. “Most illustrators simply can’t afford to dedicate that much time to one project, not when the sector is this small and you’re never certain one of the few publishers will take the risk of publishing what you have done.”

A page from Turgut Yuksel's graphic novel "Seven Deadly Days" (Turgut Yuksel)

Novel of the future

Aysegul Utku Gunaydin, editor-in-chief of Desen, part of the TUDEM publishing group, is one of the dozen houses that publish graphic novels. It released “Seven Deadly Days” earlier this year as its first graphic novel by a Turkish author.

“We’ve seen a global rise in graphic novels over the past decade, and Turkey is part of that shift,” Gunaydin told Al-Monitor. “We think the next decade will see the sector grow further and we are working to build both local production and a readership — including familiarizing children with wordless books at an early age.”

A former academic, Gunaydin has spent years examining why the form resonates strongly in countries grappling with inequality, trauma and political strain. In her view, graphic novels, particularly those with personal stories, allow complex topics to be processed visually, emotionally and without the heavy-handedness of traditional political commentary.

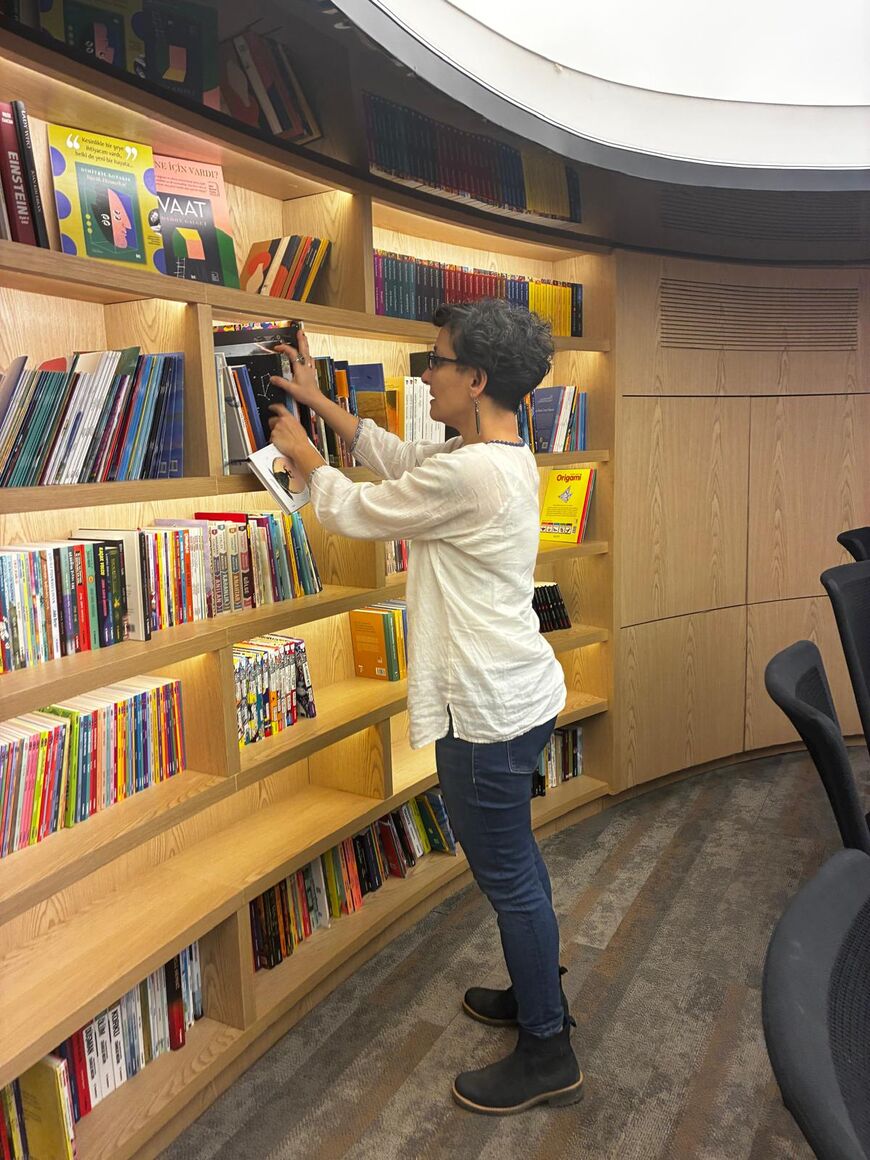

Her office shelves reflect that mission. She highlights French illustrator Fabien Toulme’s “Hakim’s Odyssey,” the story of a Syrian refugee and former car mechanic whose Mediterranean crossing is told with calm, humane lines. Nearby sits British journalist Una’s “Becoming Unbecoming,” an unflinching narrative about sexual abuse. And not far from that is Keiji Nakazawa’s “Barefoot Gen,” shaped by the author’s own survival of the Hiroshima bombing.

Aysegul Utku Gunaydin with her library of graphic novels (Nazlan Ertan)

“Turkey is building its graphic novel culture from the outside in,” Gunaydin said. “For now, it is mostly foreign authors who give Turkish readers a language to talk about displacement, inequality, sexual abuse and rape, gender discrimination, environmental angst or political strain. The stories resonate because they mirror our own, even when they come from elsewhere.”

Exposed business margins

Despite Gunaydin’s hopes for graphic novels, which she calls the “ninth art,” the figures are grim. According to the 2024 Turkey Publishers Association market report, fiction sales reached nearly 57 million copies last year, but only about 2 million were graphic novels, compared with roughly 46 million novels and 3 million poetry books. The World Population Review says Turks read 6.2 books per capita annually, less than half of India’s rate of 16 books per person. Paper, binding and printing costs are heavily tied to the US dollar and publishers say the economics of graphic novels, with their long production cycles and high-quality printing, simply do not add up.

Censorship increasingly shapes both production and distribution, especially for works dealing with gender or politics. In October, the manga-translation collective Jiangzaitoon — which had been building a Turkish-language archive of LGBTQI+ manga — announced it was shutting down after being blocked eight times by Turkey’s Information and Communication Technologies Authority.

Traditional satire faces similar pressure. In November, police raided the offices of Leman, one of the last humor magazines standing, after a Gaza-related cartoon was misrepresented online as insulting religious values. Several staff members were detained and the issue was pulled from circulation.

More support, less self-censorship

“We need a better ecosystem in Turkey so that our home-grown sector is supported and flourishes,” said Esra Kokkilic, an editor at Baobab Publishing, which translated the French political satire “Quai d’Orsay” and released Mana Neyestani’s “An Iranian Metamorphosis,” a memoir in which a single cockroach cartoon triggers a Kafka-esque descent into arrest and escape from Iran.

“We have only a handful of publishers on tight budgets. We have censorship and, worse, self-censorship. So what do some of our best creators do? They take their ideas abroad.”

Ersin Karabulut, co-founder of the satirical weekly Uykusuz, epitomizes that outward drift. He simply took “Drawing on the Edge: Chronicles From Istanbul,” his long-form account of political pressure and urban absurdity under two decades of President Erdogan’s rule, to a French publisher. After the French debut, the graphic novel was translated into several languages. A Turkish edition remains unavailable.

Similarly, Ozge Samanci’s graphic memoir, “Dare to Disappoint: Growing Up in Turkey,” shaped by the cultural aftershocks of the 1980 military coup, was first released in the United States by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Unlike Karabulut, Samanci eventually saw her book translated into Turkish by Karakarga, bringing home a story after it had traveled through six languages.

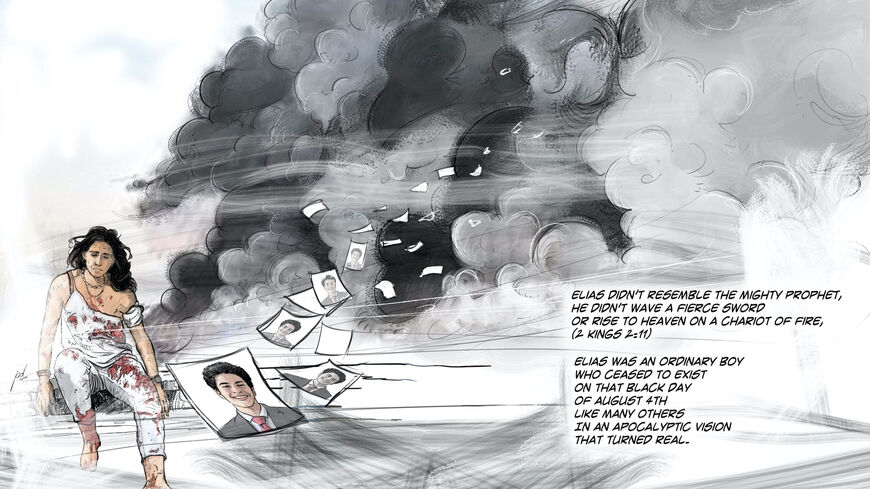

A similar outward path is visible in “Turkish Kaleidoscope,” the collaboration between anthropologist Jenny White and veteran illustrator Ergun Gunduz. Based on oral history interviews about the political violence of the 1970s and linked to today, it blends real testimony into composite characters rendered with meticulous period detail. Published by Princeton University Press, it has become a classroom staple abroad.

More collaborations

Cross-Mediterranean collaborations may soon become more common. In November, the French Cultural Center in Izmir opened the exhibition “Breaking the Mold: Comics and Migration” alongside workshops and talks by French and Turkish practitioners. “I wanted to approach Mediterranean migration not through fear or tragedy, but through creativity,” said Juliette Bompoint, the center’s director. “My hope is that it opens the door to partnership — French writers working with Turkish illustrators, or vice versa — to tell stories from different shores.”

For all its challenges, the sector is not without resources.

Publishers speak of building new distribution channels, strengthening libraries, expanding comics workshops for young artists and integrating visual storytelling into school curricula. Some also call for public-funding schemes similar to those in France.

But in the country that ranks 158th among 180 in the World Press Freedom Index 2024, publishers are afraid of taking a risk. “We steer clear of gender issues, religion and anything that would be interpreted as belittling the Turkish state,” admitted a publisher who asked not to be named for this particular quote.

“Perhaps what we need is more courage,” said Yuksel. “More courage from writers, publishers and readers themselves.”